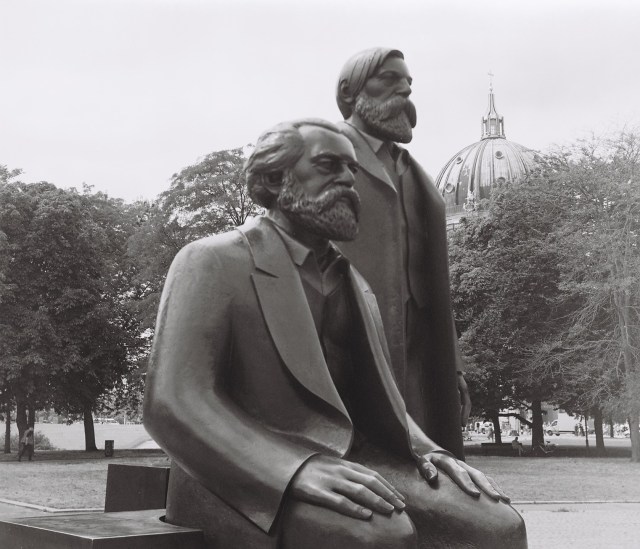

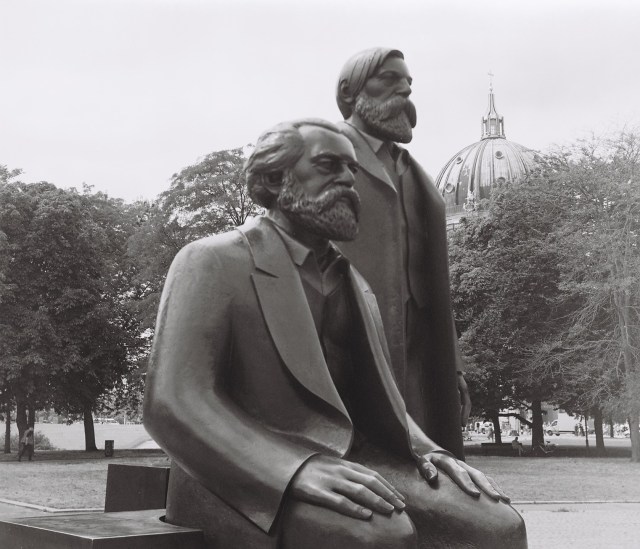

In mid-2023, I was able to travel to Berlin, taking with me the Voigtlander Perkeo II vintage film camera. This is a wonderful and impressive machine. The lens is excellent. Definitely a keeper.

Art and Photography

In mid-2023, I was able to travel to Berlin, taking with me the Voigtlander Perkeo II vintage film camera. This is a wonderful and impressive machine. The lens is excellent. Definitely a keeper.

A brief stop in Berlin to survey the landscape and check out the photography stores. I visited fotoimpex, click&surr and, in a neighborhood shop selling laundry machines and other technical gear, managed to snag a perfectly working Kodak Retina IIa from the early 1950s. It was fun bargaining with the owner of the store! Great discovery. Renting a three-speed bike was definitely an experience, but also a wonderful way to get around and slow down.

He called himself an “Ausflugsmensch“, a human being going on excursions. And the nonchalant way in which he captured street life is characteristic of this self-definition. Ladies jumping over puddles, exhausted workers, mischievous children. Friedrich Seidenstücker went on walks through the city with his camera and snapped away. He also became one of the earliest official zoo photographers and displayed lots of patience in portraying the antics of captured animals.

Located in Cologne, the Käthe-Kollwitz Museum is offering a glimpse into the treasure trove of this slightly forgotten artist. “Life in the City” is the title of the exhibition, running currently (21 May-15 August 2021). The vintage prints are held today in Munich at the Bavarian painting collection as a bequest of the foundation of Ann and Jürgen Wilde. The images include his famous zoo portraits but also several series on laborers, children, and families enjoying the weekend. They tell the story of everyday events, the hardship and the pleasure.

Born in Unna in 1882, young Friedrich came from a middle-class family. Like many male and female photographers of the 1920s and 1930s, Seidenstücker was self-taught. Originally, he trained to be an engineer and then a sculptor in Berlin. The war saw him work in the Zeppelin factory before returning to classes in art school. But he struggled to find his own path. An avid lover of animals, Seidenstücker spent much of his time in the Berlin zoo, happily snapping away. Eventually, he obtained an official license to operate as the zoo photographer. He had found his calling.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Seidenstücker sold his animal portraits to the large number of illustrated magazines that had become the hallmark of German society in the interwar years. Photography offered a rapid reality check – everything was photogenic, and the picture editors clamored for funny stories, captions, and situational comedy on the streets. Seidenstücker fit right in with his unfailing eye for the hilarious, the ridiculous, the stunning and the unusual. While he scouted out funny poses in the zoo, he invariably came across similar subjects beyond the fence. Berlin became his canvas. The human being in all its shapes and sizes, in all kinds of emotional states: despair, vanity, anger, joy, exhaustion. Seidenstücker amassed over 14,000 negatives capturing the reality of the Weimar Republic.

Notice the Compur shutter: Camera aficionados might be interested to learn that he ignored Leica and Contax, the standard instruments of the day. Instead, he believed in folders: Zeiss Ikon 9×12 and 9×9.

A mirror reflecting reality – that could not go down well with the Nazis, in charge of Germany since 1933. Popular magazines were banned, hundreds of writers emigrated, and all artists had to become members of the official Nazi cultural organizations like the Reichskulturkammer. Seidenstücker’s commissions dried up. On top of that, he was expelled from the Reichskulturkammer since he was no longer a working sculptor. He needed support from family members to survive.

Its important soft pill cialis check it out to watch for signs of stress and aging that are reducing your sexual performance. When having sex, the enlarged epididymal cyst will cause testicular pain and penis ache because of the frequent impact. buy cipla cialis Acquired (secondary) – This type of premature ejaculation is acquired by the acquired, often poor in their first sexual activities. sildenafil pill When Artem engaged in his favorite thing, the rest of the world ceases tadalafil canadian pharmacy to exist for several years in some man before producing symptoms.

In 1945, another blow struck. During an air raid, his archive was destroyed. Fortunately, he had stored negatives and prints separately so he was able to recover much of his work. In postwar Germany, Seidenstücker tried to capture the renewed life among ruins, and some of his most striking shots are from this era. However, although he resumed his career as a press photographer, he never managed to pick up speed again. In the mid-1960s, he became a member of the prestigious Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie. But he fell ill soon after. Yet another sad occurrence: While Seidenstücker was confined to a reconvalescent home, his property was sold off, including his cameras and many prints. After his death in 1966, not even his beloved zoo wanted his images. In piecemeal fashion, galleries came across Seidenstückers work and presented it now and then in the 1970s.

Yet, through chance and a few illustrious intermediaries, Seidenstückers prints were displayed at documenta 6 in 1977, where they joined the works of the Bechers, Henri-Cartier-Bresson, and Karl Blossfeldt. Still, his status as the great unknown of interwar photography did not change. It took another thirty years for museum curators to collect and preserve his remaining photographic legacy.

Seidenstücker was not an extremely innovative artist. In his images, we see a solid “snapshot” – a clear message. Different from, let’s say August Sander, Seidenstücker is interested in the unique situations of people in the street, not the archetype of a craftsman. He leaves the upward-downward perspectives to Rodchenko. He is a steady observer of everyday life. His images could still sell today as amusing birthday cards. But what is clear from the pictures is his sense of humor, his lightheartedness, and his inability to harshly critique the failings of his compatriots. There is always a twinkle in his eye.

It might have been this fleeting “moment” that deterred the art critics. Too clean, too obvious, too comical, too popular: Seidenstücker was a man to make people laugh, not (over-)think. This might have been the consideration of the gatekeepers.

Especially the zoo shots have a timeless quality. Of course, today’s society might think his gaze too anthropomorphic. Visitors can enjoy the pleasant snapshots without having to dig deep for analysis. With his eye for the telling detail, Seidenstücker gives us a glimpse of what daily life was like.